Question: What’s the difference between small boys and wild horses? Answer: Not very much.

That’s what Darrell Brown, author of One Father’s Journey to Raise Confident, Connected, Compassionate Boys, learned from the world-famous “Horse Whisperer” in a meeting that would have a profound influence on the way he raised his sons. Here, Darrell recalls what happened in that fateful encounter that taught him why “being a father is the best personal development course you’ll ever do”.

“About 10 years ago, I got to work for a couple of days with Monty Roberts. That name might not mean anything to a lot of people. But Monty is probably better known as “the Horse Whisperer”. He’s the guy who Robert Redford played in the film.

Monty is in his 80s now. But at the time, he was travelling all over the world doing 300 shows a year. How it worked was that his team would call ahead to equestrian centres in the cities where they were hosting an event. Monty got them to find people who owned horses that were the worst of the worst. He wanted the horses that you couldn’t put a saddle on, that you couldn’t ride, that you couldn’t do anything with. Those were the horses that he’d work with at the event.

My assignment was to film this short doco with Monty. I remember the first day I got introduced to him, we were chatting for a while and he said to me, “You got any kids?” I told him I had two little boys who were both toddlers. Monty looked at me and said, “Well, they’re a little bit like wild horses, aren’t they?”

What happened over the next two days was fascinating. One woman brought her horse into the auditorium and she said, “This horse won’t go into its float, so for me to take it anywhere, it takes about three hours. I usually need two or three big men to get it on the float.”

Monty said, “Well, what if I said that in about an hour from now that horse will walk into that float by itself?”

“Well, that will be some sort of a miracle if you did that,” the woman said.

Then Monty said to the owner: “Tell me everything you know about this horse. I want to know his background, how he was treated, what he was like when he was younger. Tell me about what he will do and tell me about what he won’t do.”

At first, Monty just looked at this horse and walked around it. He spoke to the horse but didn’t approach it. He told the audience what he thought the horse was doing and thinking. He observed the horse’s patterns of behaviour. Then he said, “You’ll have noticed that I haven’t gone over to the horse yet, I haven’t touched the horse at all. That’s because the horse hasn’t invited me into that space yet. You’ve got to wait for that sacred moment when that horse invites you in.”

He kept on talking. Then he’d walk close to the horse and the horse would move away.

But Monty just took his time and eventually when he got up close, he explained: “You wait for this moment now when the horse’s ears will just drop back.” Then he puts his hand up and the horse touched his hand with its nose.

“That’s the moment we call ‘join-up’,” Monty said. “Join-up is that moment when the horse invites you into its space. Until you have that relationship, nothing will work with the horse but force. Until then, that’s the only thing that will get the horse to obey.”

“Getting to join up might take a while with some horses,” he said. “But I just have to sit back, read the horse, observe it and communicate with it until I get to that place.”

Then Monty did this thing where he would sort of lead the horse towards the float and then push it back two steps and say, “No, you’re not going in there.” Then he’d bring the horse towards the float again and push it back again. It was like he was doing this kind of reverse psychology with the horse. Eventually, he lead the horse all the way up on the float and pushed it all the way back down again.

Finally, he said to the woman, “Are you ready to watch your horse walk onto his float?” He turned his back on the horse and stood there, and the horse just came up and nudged him in the back and he walked all the way up the ramp into the float and the horse just walked in with him.

“You will never have to worry about floating this horse again,” Monty said to the woman. “From now on, he will just walk straight in.”

Over the next two days I saw Monty work with all kinds of horses. He worked with a horse that was terrified of plastic, but Monty built a relationship with it until he could put a tarpaulin on its back. I saw him work with a horse that would never take a saddle, but Monty managed to put a saddle on it and ride the horse within half an hour. He did all these amazing things. There was not a single horse that he could not work out how to communicate with.

On the very last day, Monty walked into the middle of the auditorium, put down a chair and spoke to the crowd.

“It was my dad that taught me about horses,” he said. “When I was a young lad, my dad had a big ranch. Owners around the land would bring us their wild horses and I used to watch my dad and his trainers whip and beat these horses. Finally through force and aggression they would break their spirit. They would put a saddle on them and they would give them back to the owners as a broken horse that was ready to obey and do whatever they wanted.”

“Deep down, I always thought that wasn’t the best way to communicate with a horse. So I started working with horses on my own away from the ranch. And I found a way of communicating with horses that was a lot more effective – like I’ve shown you over this weekend.”

“One day when I was 17, I said to my dad: ‘I think I’ve found a way of getting horses to comply and to do what you want in a fraction of the time without all the men and all the aggression.”

“My dad looked at me and said, ‘No, don’t be stupid. This is the way it’s done and this is the way it’ll always be done’.”

Monty said it wasn’t long after that that his father died. He never got to see the way that Monty was able to communicate with horses in a way that was completely different, using compassion, patience and understanding.”

Monty said: “The interesting thing is my dad raised his children the same way he raised his horses. My dad used a lot of aggression, he used to hit us, he used to force us to comply.”

That was just the way his father was taught, he explained. Back then, a lot of men raised their kids that way. “You got to understand a lot of these men came through a war, they came through some pretty tough times,” Monty said. “In order to deal with that, they shut themselves off emotionally. What they did know was that you could get people to do things by using force.”

Monty said: “If you understand what I’ve done with horses, you’ll understand that raising horses is a lot like raising children. Our kids are born with wild spirit, with adventure. Our job isn’t to break that spirit. Our job is to communicate with it.”

As Monty was telling this story, I was looking around the auditorium and there are people with tears just running down their face. They knew that what Monty was saying was so right and so important.

Monty said, “We live in a world where, particularly with young boys, we don’t understand their wild spirit and their sense of adventure. We don’t understand why they don’t want to sit still in class. So we try and medicate that out of them. We try and discipline it.

“But you don’t need to do that at all. You just need to communicate with that spirit, you need to talk to it, you need to invite it into the outside world. Boys are meant to run, their life isn’t meant to always be in a book or a classroom. Their life is out there in the forest, in the hills and in the rivers. With boys you need to let them run, they’re born to be risk takers. Your job is to guide that and speak to that and communicate with that. You need to watch it and try and understand it.”

“Just like with the horse, you got to be invited in. You’ve got to look for certain patterns and try and find a way in. Parenting is a dance and being a father is the best personal development course you’ll ever do. It’s about you learning how to find ways to communicate with their spirit and guide it and bring love to the experience.”

Monty’s story was so powerful for everyone in the room. It was just this beautiful metaphor for raising your own children – that to get them to follow you into the float, you didn’t have to do it by force. You could do it by modelling values to them, by modelling integrity, by modelling what healthy masculinity looks like, by modelling what patience looks like. You can tell your kids what you want. But if you model those things in their vicinity, then they’ll become who you are.

I never forgot that story. My sons were about three and four at the time and that story just spoke directly to my soul. My wife Jules and I used to love our boys’ spirit and their sense of adventure. We thrived on it. Our sons gave us an energy that we had lost ourselves.

As parents, you learn to act appropriately in the adult world and we do lose that sense of adventure and risk-taking and playfulness that we all need. I think if we actually managed to hold onto that, we’d become better entrepreneurs, better adventurers. But we’d also have a lot more fun in our own lives too.”

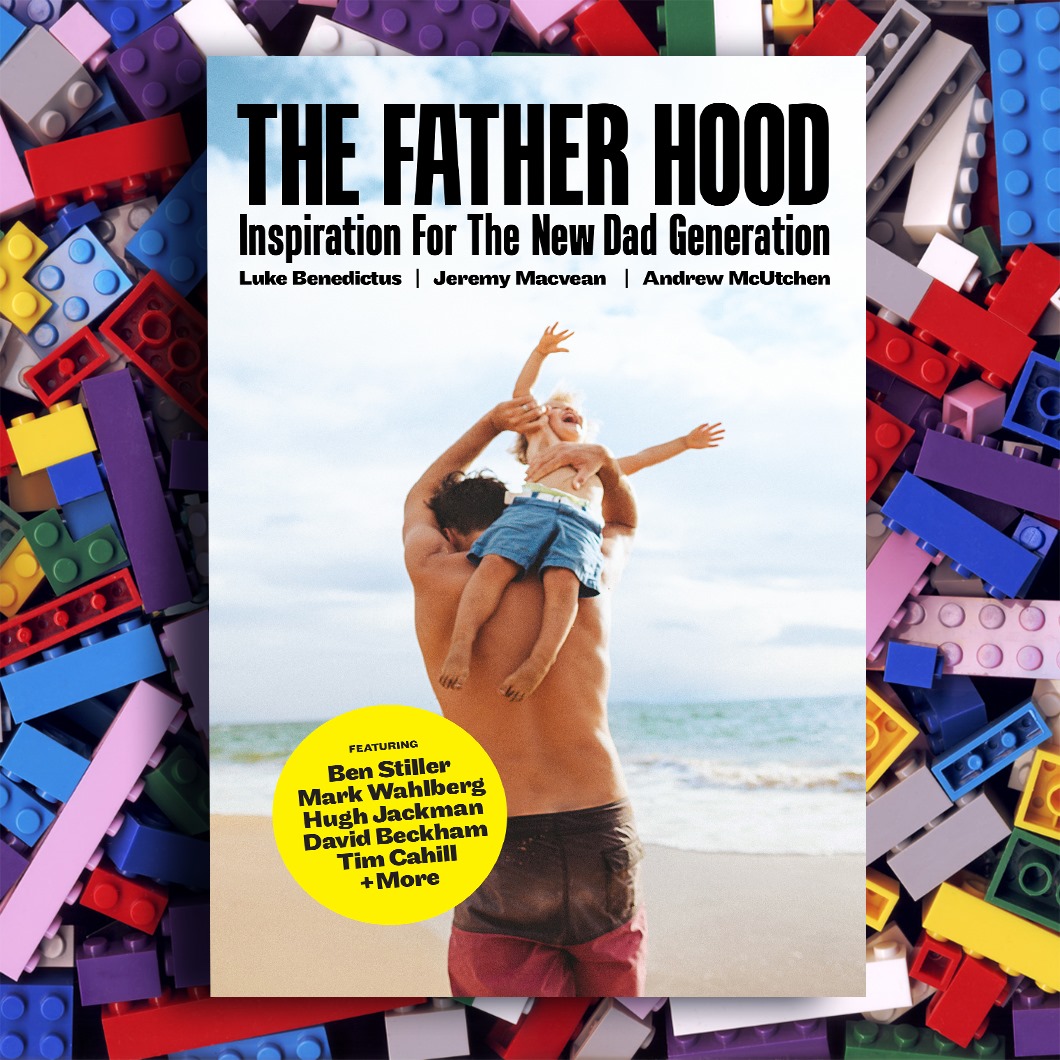

This is an extract from The Father Hood: Inspiration For The New Dad Generation. Buy it here