When it comes to fatherly know-how, Steve Biddulph is a Jedi master. The retired psychologist is one of the world’s leading parent educators and his books, including The Secret of Happy Children, Raising Boys, and 10 Things Girls Need Most are in four million homes and 31 languages. Here, Steve shares a personal story from his own life that highlights the generational shift in fatherhood and shows why dads today have an incredible opportunity to develop closer relationships with their children than ever before.

At the age of 74, my father was diagnosed with cancer of the liver. Within 12 weeks he was dead. With the help of modern pain control, we made good use of the time – talking, hanging out, getting ready. Which isn’t to say there weren’t times of racking sorrow, or confusion and pain, but for the most part, it was a peaceful dying. Here, he shares a deeply personal story from his own life that shows why dads today have it

Shortly before the morphine began to carry him beyond reach, my father recounted, out of the blue, an incident from my early life. What he told me, haltingly, seemed to embody the struggle men have had to wage, in order to be allowed to fully experience fatherhood. Days after my birth in 1953, when we had returned from hospital to the grimy Yorkshire town where we lived, my father took me out in the pram, perhaps to give my mother some peace. He bundled me up and set off towards the town centre – I imagine his choice of route involved some element of pride, but perhaps it just offered more shelter from the icy winds. As he entered the high street, he noticed passersby reacting oddly. Some were openly scornful; some looked amused. But the final straw came when a group of children, unoccupied, began to follow along and taunt him.

What were they saying, I asked. He remembered the words exactly: it was a kind of chant. “Your dad’s your mum,” he said, and his voice slipped back into the north-country vowels the kids used all those years ago. In the end, the whole thing had been too much for him – he was a shy man at the best of times – and he turned off down a sidestreet, and went quickly home.

As my father closed his eyes to rest, I pictured the vulnerable-looking young man I had seen in family photos colliding headlong with the tight role definitions of 1950s working-class England. He was a “new man” 50 years before his time. And the thought occurred to me that he could hardly have been unique in this. How many millions of young fathers, animated with the joy of new fatherhood and the instinctive urge to tenderness, had, through social pressures, clamped down on their feelings? How many, even worse, had turned them into harshness and violence?

That my father had chosen to tell this story from the beginning of my life at the end of his own seemed loaded with meaning. He had read my books on parenthood. He had sat with gruff pride at the back of my lectures on healing the rifts between fathers and sons. He could not have failed to take some of this personally; he and I had not always been on good terms, and our peaceful closeness was only a recent and hard-won possession.

What he was trying to tell me was hardly rocket science: it was a way of saying, “I tried, son.” But my father more than tried: he brought our family to Australia against all the odds, he remained an affectionate, playful, sacrificing parent in a turbulent age. He wasn’t all I wanted, but what father ever was?

But this all went beyond the personal. He was a trade unionist, as his own father had been. He was attuned to injustice and the need to fight for what you believe. We don’t blink today at a father pushing a pram, though it’s still new enough to be heartwarming. It sounds trivial, but what it represents is a revolution of the deepest kind. Involved, hands-on fatherhood was almost crushed out of existence in the industrial era: but it fought back. Fatherly love has survived.

I would like to be able to say that the crushing of fatherhood is a thing of the past. But today’s men are still being riven from their children. It is not jeering street urchins so much as a political and economic climate that drives longer working hours and devalues both mothers and fathers in their primary role, while claiming to be family-friendly.

Families need a socially supportive context. The government still presides over policies that see human beings primarily as economic units. The government drags its feet on decent paternity and maternity leave, would prefer single parents working on checkouts rather than spending time with their toddlers at home. I fear there will be a new generation of young men and women who feel estranged from their parents if we do not turn this situation around. The Australian father of today still has a battle on his hands to stay close to his children, but the signs are good. A father’s heart isn’t easily silenced.

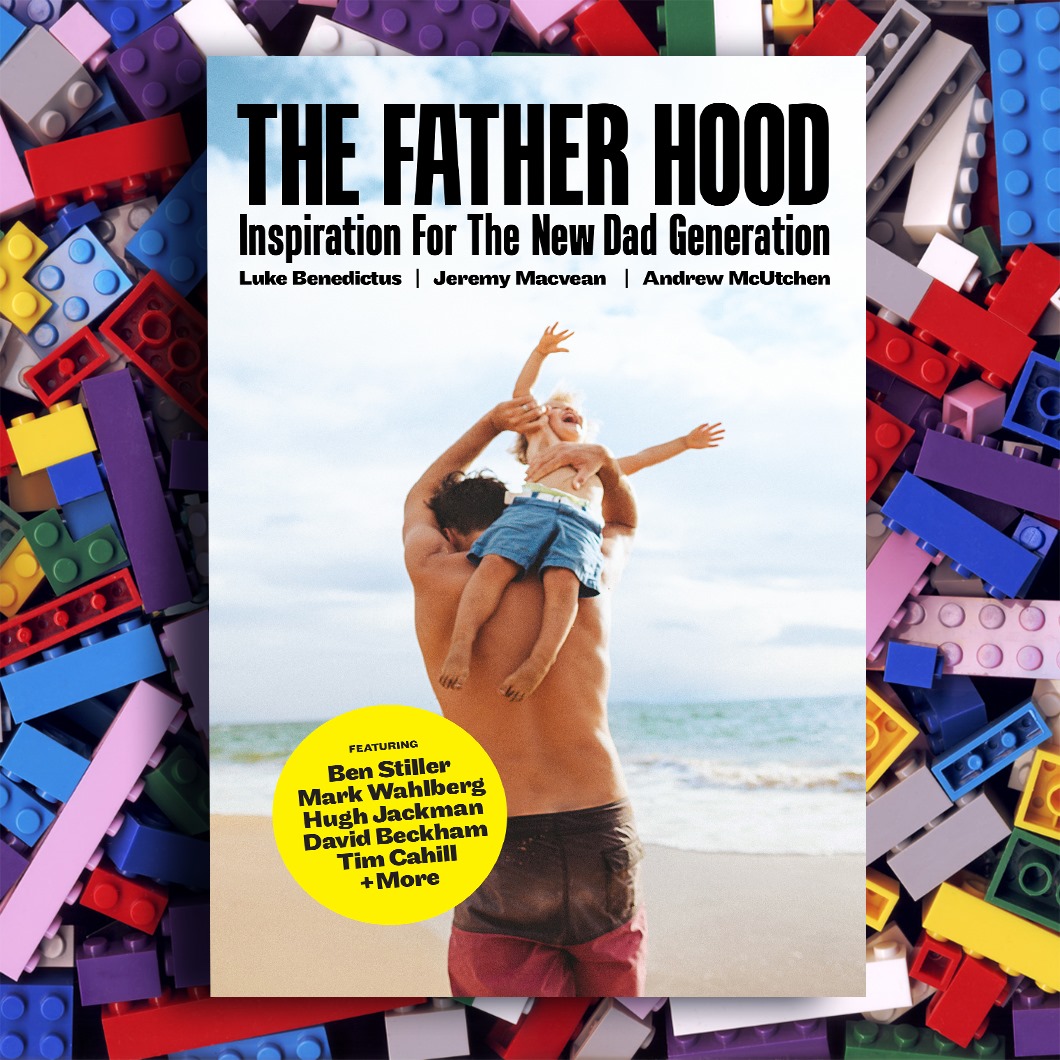

This is an extract from The Father Hood: Inspiration For The New Dad Generation. Buy it here